This is the one question that writers allegedly dread being asked. But as a writer myself, and a reader, it’s the question I would most like to know of another writer.

Some authors are inspired by a place, or a period in history, some by personal experience, others by a real event read about in a newspaper (or these days on social media). As for me, my ideas always begin with people.

The first book in my Modern Women series, The Awakening of Claudia Faraday, featured a 50-something society lady and mother of three whose moribund life is revitalised by her discovery of the joy of sex. The idea sprang from a short story which in itself was partly inspired by Ian McEwan’s On Chesil Beach, in which a young couple’s married life is ruined on the first night of their marriage by the bride’s deep-rooted fear of sex.

Well now, I thought, isn’t that a common experience? Not all sex entails couples panting up against a wall, or groaning and writhing in a rumpled bed. Sex, particularly for women in the past, was not necessarily regarded or expected to be either joyful or particularly fulfilling. Sex was for procreation only. We have our forefathers (and –mothers) to thank for that.

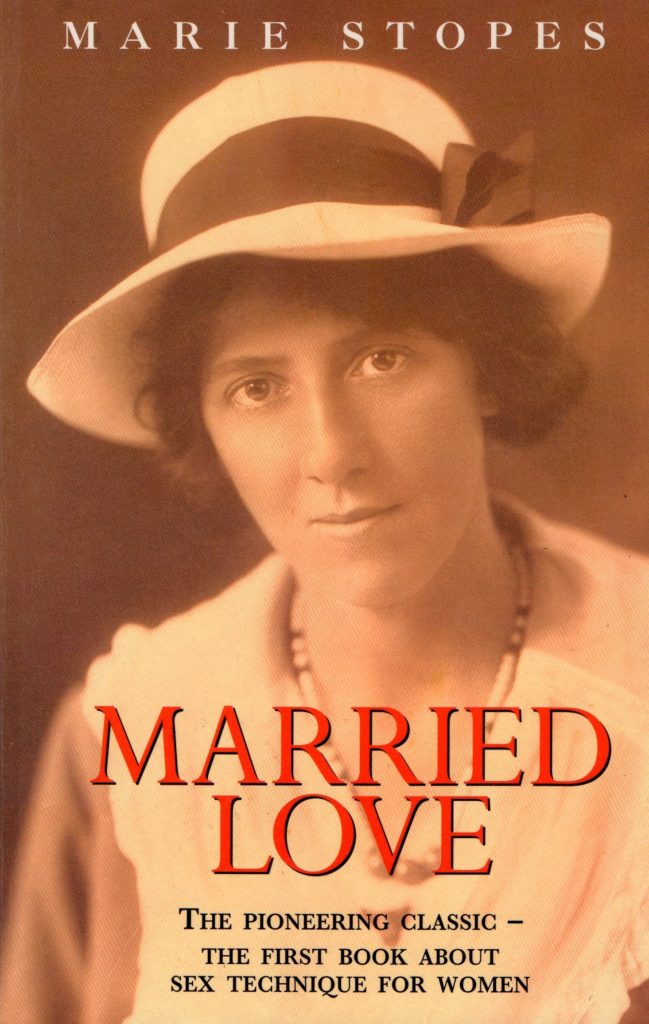

When I expanded my short story into a full-length novel I decided to set it in the Roaring Twenties, a time of revolutionary change for women: off with the corsets and the inhibitions, in with bohemianism, free sex and Marie Stopes. It was Ms Stopes who first posited (in her book Married Love) the idea that sex could be fun for its own sake and not just for the continuation of the species; who actually mentioned the c-word in print (not that c-word). In my book it was the discovery of the outlandish idea that sex did not necessarily mean lying back and thinking of England that opened Claudia’s eyes to the changing world around her, which in turn led her to realise life can begin at fifty.

Then, since one thing inevitably leads to another, subsequent books in my Modern Women series featured women who’d appeared in the previous book. So Prudence, Claudia’s free-wheeling best friend, became the subject of book two, The Purpose of Prudence de Vere; and Violet, Prudence’s unhappy suffragist friend, the subject of book three, The Makings of Violet Frogg and again of book four, Mrs Morphett’s Macaroons.

As I immersed myself first in the Roaring Twenties and then in the Victorian and Edwardian periods – the books went backwards chronologically – I became more and more intrigued by the role of women in those societies. The series title ‘Modern Women’ only occurred to me some way down the line, as I realised Claudia, Prudence and Violet – and indeed Merry and Gaye, two actresses who feature in my later books – were all in their different ways bucking the trend of the worlds in which they lived. They were not campaigning feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft or Emmeline Pankhurst. But they managed, in their different ways, to find the means to live their lives as they wanted irrespective of what was expected of them; whether that meant partying with bisexuals in a flat in Parsons Green (Claudia), or proposing marriage to John Maynard Keynes (Prudence), or breaking away from an unhappy marriage to join the suffragist movement and work for a living (Violet).

Quiet revolutionaries all.