As we all know Valentine’s Day is an invention created by commercial enterprises to sell cards, flowers, champagne and exorbitantly expensive nights out.

All that said, it’s good to celebrate love – not necessarily just romantic love, but love of any kind. Here for instance is a poem I just constructed about my grandson. I am not – as is blindingly obvious – a poet. But there is something about watching a small person grow that brings out the McGonagall* in me. So here goes:

FOR SONNY

I’m looking at you.

Yes, I’m looking at you, kid,

In a way I never did with my own.

(My own kids, that is:

Not enough time, too much anxiety,

Too much of everything.)

But you I can watch without judgement

Or criticism or anxiety,

With time, and simple fascination and wonder,

As you grow and learn and become

Your very own person.

But there is one thing you both have,

Both you my children and you my grandson,

You have my total, undivided, unconditional love.

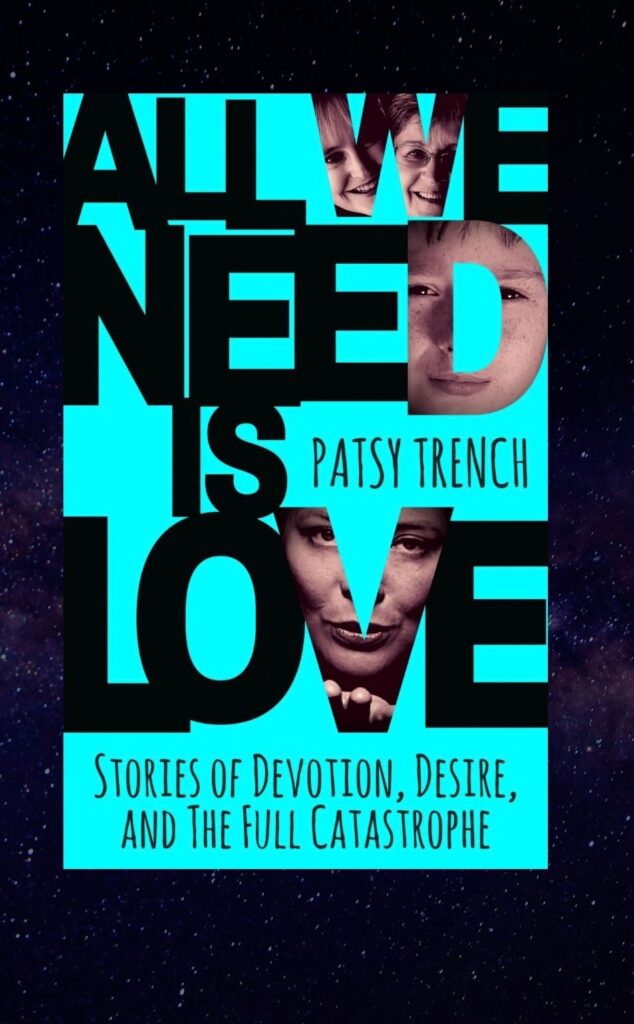

As anyone who knows me will confirm that is about as sentimental as I am likely to get. For a different take, or series of takes, on the thorny business of love, have a look at my collection of short stories about love in adversity.

Available on Amazon, Nook, Kobo & Apple Books

*William McGonagall was a Scottish poet in the ‘doggerel’ style. He was widely regarded as ‘the worst poet in British history’ (to quote Wikipedia). His life, incidentally, was fascinating, and he was remarkable for his total belief in himself and whatever he chose to write or to do, no matter how weird and unlikely.

Happy Valentine’s Day everyone.

Patsy Trench

14 February 2023