As any family historian knows, we live for these breakthrough moments, but they come along very rarely.

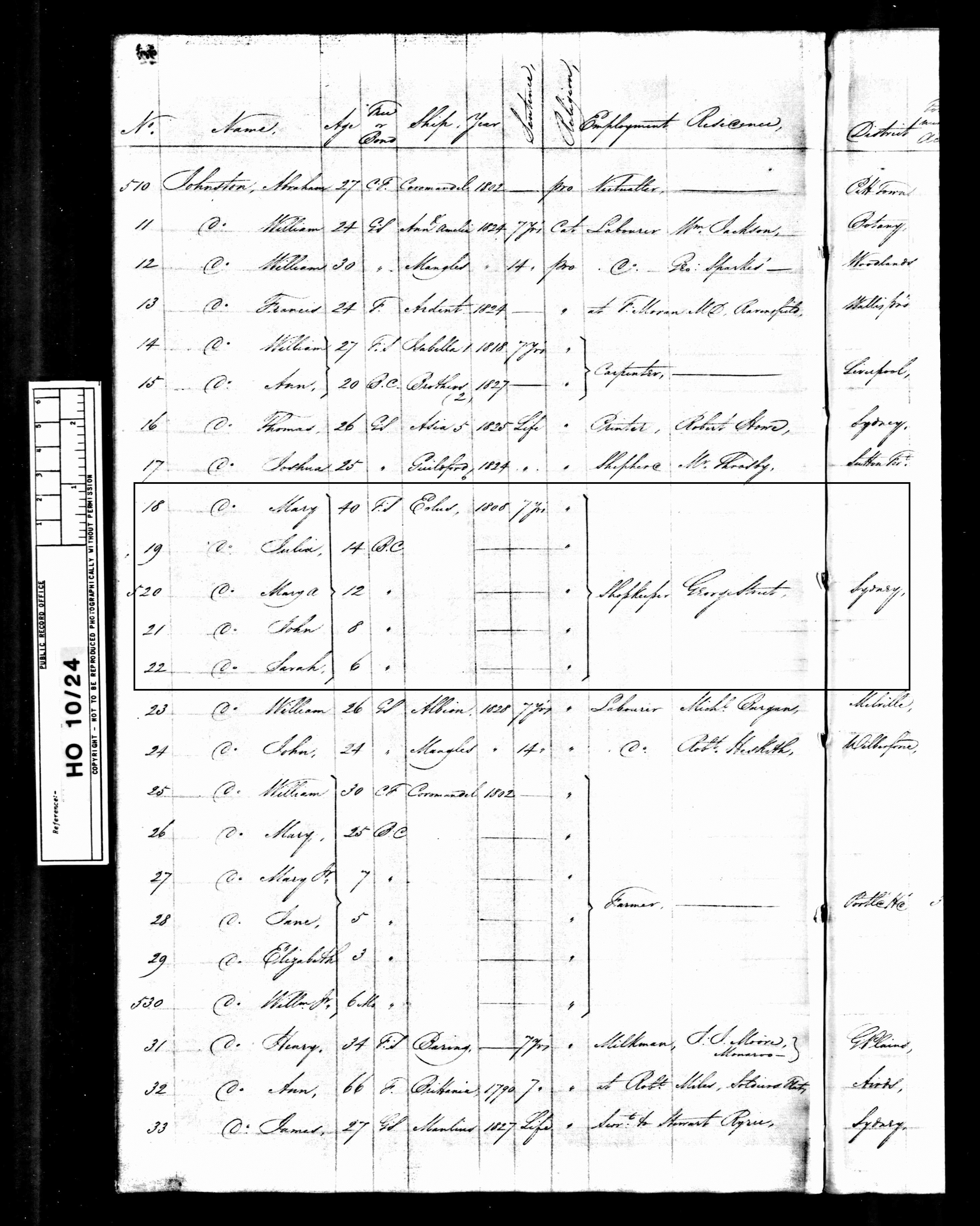

My three times great grandmother was a convict called Mary Moore, transported to New South Wales in 1808 for 7 years for stealing items valued at £1.15s.6d. A few years after her first husband – my three times great grandfather – died she married again, another convict, Irish this time, called Robert Aull, and took her four children to live with him and his five children in Richmond, where he bought the license for a pub on what they called the “Yellow Munday’s” (Yarramundi) Lagoon, which he named the General Darling.

As tended to happen in those days once she married Mary disappeared from the records. She had appeared in a previous census as a shopkeeper, but from the date of her marriage in 1829 she vanished off the apparent face of the earth. Two niggles stopped me from thinking she lived happily ever after with her new hubby: the 1841 census – where she did not appear to be living with him – and the fact that she was buried in the name of Mary Johnson, after her first marriage.

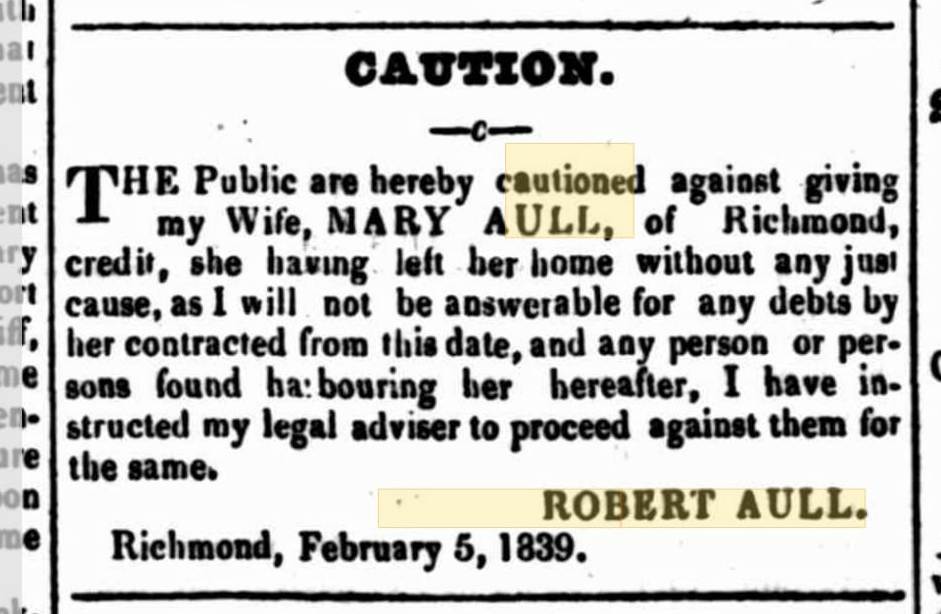

I was searching for Robert Aull in Trove – the Australian digitised newspaper website – and had got to the stage where all that was cropping up were the odd Robert and ‘aull’ in place of ‘all’ when Eureka: I came upon the notice, inserted in The Colonist three times and The Sydney Morning Herald once by her hubby, announcing her sudden and obviously unwelcome departure from the family home. I’ve no idea where she went, but the tone of the ‘advertisement’, as that is what it was, makes it very clear Robert was not pleased; worse, he makes her sound like a runaway convict, or even a stolen cow, threatening anyone found ‘harbouring’ her.

The moral of the tale is keep looking: even when you think you’ve exhausted the records there may just be a nugget of gold awaiting you.