Warning: this can become an addiction.

I only began taking interest in my Australian family history in my later years. On my semi-regular visits to Australia – where I once migrated to and where half my family still lives – I visited my one surviving aunt, who lived in a retirement home in North Sydney. By way of making conversation I asked her about our family history, which she had spent her retirement years researching, and how our family came to be in Australia in the first place.

The story she told me was remarkable. Our earliest Australian pioneer was a widow in her fifties called Mary Matcham Pitt, who migrated with her five children to what was then known as New South Wales in 1801, just 13 years after the country had been purloined by the British as a penal colony and at a time when it was considered by its earliest colonial inhabitants as unfit for human habitation.

So to cut a very long story short, I spent the next seven years travelling back and forth between my home in London and Australia researching Mary and her family’s background both here in England and in New South Wales, in order to produce my first book, which I named, appropriately:

The research included investigating the earliest history of colonial New South Wales, a fascinating and unlikely story in itself and posed several obvious questions, viz:

- Why did over 1000 people, mostly convicts, sail to the opposite corner of the world to establish a penal colony in a country whose shores had only been sketchily mapped (by Captain James Cook) several years earlier?

- Why did they not first send out a research party of experienced explorers and navigators, not to mention builders and farmers?

- Why did my four times great grandmother choose to leave her family home to live in such a place, among convicts?

- How did the colony survive against all the odds?

The answer to the first two questions is, most likely, time. It would have taken at least a year to sail to New South Wales and back, not allowing for time spent reconnoitring the country itself, and Britain’s prisons were full to bursting.

The answer to the third question is as far as I have been to make out (with help from my aunt) contained in my first book.

The answer to the last question is a remarkable man called Arthur Phillip, first Governor of Australia, whose sheer tenacity and iron discipline ensured the earliest colonists survived near starvation, rebellion and general discontent in the colony’s first two years during which they received neither provisions nor messages from the old country.

Beware of addiction

Family history can become addictive. My forays into colonial Australia’s beginnings so enthralled me I was inspired to continue my researches into my subsequent Pitt ancestors and in particular of my two times great grandfather George – pioneer farmer, auctioneer, stock and station owner and Mayor of north Sydney. This second book took me only five years to research and write and I called it

Research into your family history is never-ending

Early colonial history is well documented in Australia and researching family history there is very popular. Apart from the libraries – every small town has one and many of them have a dedicated family history section – there are website such as Ancestry and Findmypast, and the wonderful resource known as Trove, where you can delve into newspapers going back to their beginnings, and for free.

Here in England I spent many happy and occasionally frustrating days at the British Library, the Dorset Records Office and the National Archives in Kew in south London, the latter of which contains the original indictments of my convict ancestors – imagine what a thrill that was.

Family history has added to – and on occasion corrected – the general understanding of Australian colonial history, views of which have altered over the years depending mostly on the federal government of the time. For example, and I’ve experienced this myself in my sporadic trips there, the ‘black armband’ version – where the darker side of what many now call the ‘invasion’ of a country by a colonial power – was once scorned by the (right-wing) Liberal party in favour of what they considered a more positive picture of pioneering enterprise, bravery and fortitude on the part of the early settlers. This ‘history wars’ is fascinating in itself, and continues to evolve as the decades roll by.

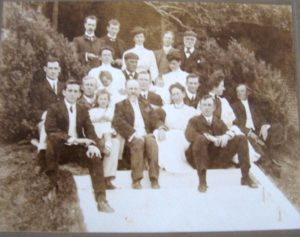

Family history is above all invaluable as a chronicle of everyday lives. Professional historians tend to focus on the famous and significant, but most people are neither famous nor necessarily significant. It is the ordinary people who make the world go round, who drive the buses and trains, farm the land and man the supermarkets. It is the people in the background of the picture of world history who not only oil the wheels of daily life, they would remain largely forgotten and unrecorded were it not for family historians. We have a responsibility to get it right.

Coming soon: how to write and publish your family history.