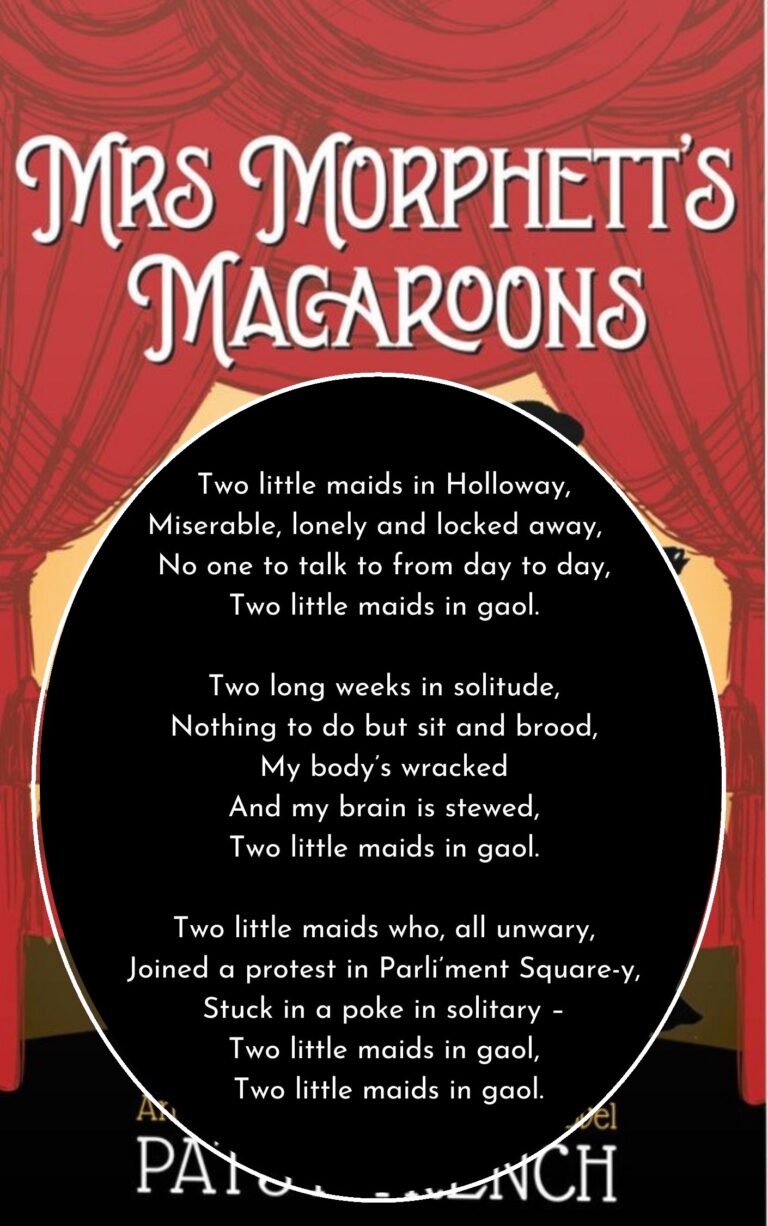

An extract from my forthcoming novel ‘Mrs Morphett’s Macaroons’, as performed by the redoubtable duo, Merry and Gaye. With apologies to W S Gilbert (and Sir Arthur Sullivan).

It celebrates the glorious OTT fashion for hats in Edwardian England. (And the fact that one of my characters is a milliner.)

MERRY:

I am the very model of a modern lady milliner,

I own a little hat shop off the Strand – you may have been in there,

My clients are exclusively the cream of our society,

I’m known for my discretion and my taste and my propriety.

I know the latest fashion and I’d say that I’m ahead of it,

You’ll never find a hat that’s out of style, I just get rid of it,

I’ve simple hats and fancy hats with trimmings and with featherers,

I’ve hats for all occasions and for every kind of weatherers.

GAYE: (accompanying the words of the chorus with a strange little bobbing motion)

She’s hats for all occasions and for every kind of weatherers,

She’s hats for all occasions and for every kind of weatherers,

She’s hats for all occasions and for every kind of weather-weather-ers.’

MERRY:

Each model is unique, you will find there’s only one of it,

Fads and mass production, I’ll have absolutely none of it,

No Merry Widow nonsense and no passing whims or silliness,

For I’m the very model of a modern lady millin’ress.

GAYE: (chorus)

No Merry Widow nonsense and no passing whims or silliness,

For she’s the very model of a modern lady millin’ress.

MERRY:

I’ve curly brims and floppy brims and hats completely brimless,

Panamas with ribbons on, irregular or rimless,

I’ve Buckets, I have Cartwheels, I have Gainsboroughs with flowers on,

Tricorns, tam o’shanters, and a cloche with Eiffel Towers on.

Wedding hats and party hats, Derby hats and toques,

I’ve hats from off the shelf, made to measure and bespoke,

I’ve bretons and I’ve turbans, on the straight or asymmetrical,

Berets plain or stripy or with patterns diametrical.

GAYE:(chorus)

Berets plain or stripy or with patterns diametrical,

Berets plain or stripy or with patterns diametrical,

Berets plain or stripy or with patterns diametri-metrical.

(The tempo of the music slows)

MERRY:

Each bonnet is a statement, every beret tells a story,

A hat is so much more than just a mere accessosory,

I’ve sober hats and jaunty hats, for fun’rals or festivities,

Hats for servants, mistresses, and maids of all proclivities.

There are hats to make a maiden swoon, hats to dance a reel in,

Picture hats to hide beneath or cloches all-revealing,

Boaters that will guide you in your speech and your behaviour,

Yes, a hat can be your dearest friend, a hat can be your saviour.

GAYE: (chorus)

A hat can be your dearest friend, a hat can be your saviour.

A hat can be your dearest friend, a hat can be your saviour.

A hat can be your dearest friend, a hat can be your saviour-saviour-er.

MERRY:

From the promenades of Paris to the salons of Sofia,

You’ll find my darlings perched on every noble head you see-a,

In halls of fame throughout the world my name is all-familiar,

I am the very model of a modern lady milliner.

GAYE: (chorus)

In halls of fame throughout the world her name is all-familiar,

She is the very model of a modern lady milliner.

(Images from Pixabay.com)

© Patsy Trench