A few years ago while refugees were risking their lives on the Mediterranean Australia’s then Prime Minister Tony Abbott swept in to put us to rights and tell us Europeans the problem could be solved with three words: Stop the boats.

After all that’s exactly what he had done, and his predecessor Kevin Rudd, and look how successful they’d been. By telling the refugees in no uncertain terms that no one trying to reach Australia illegally would be allowed to settle there, they were saving the lives of untold hundreds from drowning, he said. Then just to make it quite clear, those who still tried to make the journey were to be intercepted and transferred to detention centres in remote islands in the Pacific – Nauru and Manus Island – in such terrible conditions that they’d be sure to return home, and to spread the word there that trying to seek asylum in Australia was a waste of time.

Abbott’s response to being told he was breaching United Nations law was ‘I’m sick of the United Nations telling me what to do.’ The only sign that the Australian government are not 100% proud of their policy is that the detention centres are a dark secret. Not only are journalists prohibited from visiting them, anyone caught whistleblowing could face two years in gaol.

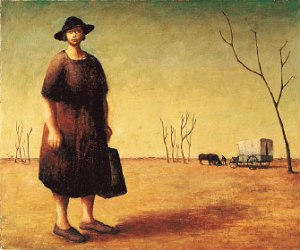

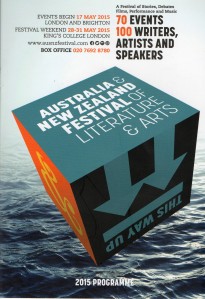

Despite this, filmmaker Eva Orner managed to smuggle cameras in to expose the degradation, deprivation and despair of the men, women and children in these detention centres. She also managed to get social workers and others who’ve worked there, most of them young, to tell their story and risk being detained themselves. To date, unsurprisingly, nobody has yet been imprisoned for spilling the beans. Her film Chasing Asylum was screened this morning in London as part of the London Film Festival. It presents its story without comment – other than from past Prime Ministers and Ministers of Immigration. It sings the praises of the late Liberal PM Malcolm Fraser, who was responsible for welcoming Vietnamese boat people back in the ’70s and who right up until the day he died still campaigned for a more humanitarian attitude towards the less lucky in the world. After all what is Australia but a country of immigration?

It doesn’t pay to be too complacent however, not if you live in Britain. By accident of geography the refugee crisis doesn’t hit us like it does the rest of Europe and North Africa. Perhaps the brave and talented (and Oscar-winning) Ms Orner could turn her attention next to Calais.